Wahlund effect

In population genetics, the Wahlund effect refers to reduction of heterozygosity in a population caused by subpopulation structure. Namely, if two or more subpopulations have different allele frequencies then the overall heterozygosity is reduced, even if the subpopulations themselves are in a Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. The underlying causes of this population subdivision could be geographic barriers to gene flow followed by genetic drift in the subpopulations.

The Wahlund effect was first documented by the Swedish geneticist Sten Wahlund in 1928.

Contents |

Simplest example

Suppose there is a population  , with allele frequencies of A and a given by

, with allele frequencies of A and a given by  and

and  respectively (

respectively ( ). Suppose this population is split into two equally-sized subpopulations,

). Suppose this population is split into two equally-sized subpopulations,  and

and  , and that all the A alleles are in subpopulation

, and that all the A alleles are in subpopulation  and all the a alleles are in subpopulation

and all the a alleles are in subpopulation  (this could easily occur due to drift). Then, there are no heterozygotes, even though the subpopulations are in a Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.

(this could easily occur due to drift). Then, there are no heterozygotes, even though the subpopulations are in a Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.

Case of two alleles and two subpopulations

To make a slight generalization of the above example, let  and

and  represent the allele frequencies of A in

represent the allele frequencies of A in  and

and  respectively (and

respectively (and  and

and  likewise represent a).

likewise represent a).

Let the allele frequency in each population be different, i.e.  .

.

Suppose each population is in an internal Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, so that the genotype frequencies AA, Aa and aa are p2, 2pq, and q2 respectively for each population.

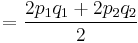

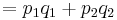

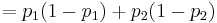

Then the heterozygosity ( ) in the overall population is given by the mean of the two:

) in the overall population is given by the mean of the two:

which is always smaller than  ( =

( =  ) unless

) unless

Generalization

The Wahlund effect may be generalized to different subpopulations of different sizes. The heterozygosity of the total population is then given by the mean of the heterozygosities of the subpopulations, weighted by the subpopulation size.

- De Finetti diagram (see Li 1955)

F-statistics

The reduction in heterozgosity can be measured using F-statistics.

References

- Li, C.C. (1955) ...

- Wahlund, S. (1928). Zusammensetzung von Population und Korrelationserscheinung vom Standpunkt der Vererbungslehre aus betrachtet. Hereditas 11:65–106.